- Home

- Treasure Hernandez

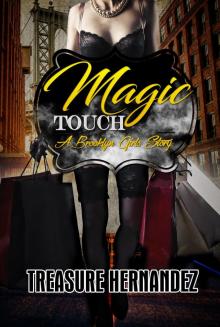

Magic Touch

Magic Touch Read online

Magic Touch

A Brooklyn Girls Story

Treasure Hernandez

www.urbanbooks.net

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Chapter 1 - New Beginnings

Chapter 2 - Learning the Ropes

Chapter 3 - Becoming a Pro

Chapter 4 - Coming of Age

Chapter 5 - Nothing to Lose

Chapter 6 - Things Fall Apart

Chapter 7 - Alone

Chapter 8 - Wrong Path

Chapter 9 - Spiraling

Chapter 10 - Out in the World

Chapter 11 - Stranger of Savior

Chapter 12 - Part of the Family

Chapter 13 - Training Day

Chapter 14 - In Deep

Chapter 15 - Turned Out

Chapter 16 - This Here Lifestyle

Chapter 17 - Karma

Chapter 18 - Another Side

Chapter 19 - Growing Up, Growing Apart

Chapter 20 - Losing It All

Urban Books, LLC

300 Farmingdale Road, NY-Route 109

Farmingdale, NY 11735

Magic Touch A Brooklyn Girls Story

Copyright © 2017 Urban Books, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without prior consent of the Publisher, except brief quotes used in reviews.

ISBN: 978-1-62286-589-5

This is a work of fiction. Any references or similarities to actual events, real people, living or dead, or to real locales are intended to give the novel a sense of reality. Any similarity in other names, characters, places, and incidents is entirely coincidental.

Distributed by Kensington Publishing Corp.

Submit orders to:

Customer Service

400 Hahn Road

Westminster, MD 21157-4627

Phone: 1-800-733-3000

Fax: 1-800-659-2436

Chapter 1

New Beginnings

Loud reggae music blared through the house and competed with the clang of pots and pans. The smell of curry and fried plantains wafted through the air so strong the aromas had dragged Simmy out of her sleep with hunger pangs. As she stretched her arms over her head and wiggled her toes, Simmy could also hear the bustling noise of the block party preparations going on outside of her window: loud Calypso music, steel pan bands practicing and, of course, the screaming of, “Ayo!” and, “Yo, son!” up and down her block, and extra noise associated with the extra people who came out to Brooklyn for their annual block party, bustling up and down the street. It was definitely a typical noisy, hot summer weekend in August.

If Simmy had her way, it would be a good weekend of partying and celebrating to mark the end of summer. She was looking forward to her last year of high school and finally graduating. Now, if she could get her hands on some money so she could buy herself a decent outfit, that would make her day.

She threw her legs over the side of her bed and sat up. Although it was the last weekend in August, the sun still blazed as if fall weren’t around the corner. Simmy fanned her face with her hands trying to make what little breeze she could.

“Who took my fan?” she mumbled, looking around the small, cramped front room where she slept.

The room was so hot, long, loose strands of Simmy’s hair stuck to the side of her face and snaked down her neck like ivy growing on an old building. Her T-shirt clung to the wet parts of her chest and back.

“They always touching my stuff,” Simmy groaned, scanning the small space to see what else her cousins might’ve touched. She sighed loudly when her eyes landed on the big gray plastic bins with purple covers that served as her dresser. A few pieces of her clothing hung over the sides and, Simmy noticed, just below the stack of plastic bins her neat row of shoes had been touched, too. Two pair were missing. A flash of heat exploded in Simmy’s chest.

“I’m telling,” she grumbled, stomping out of her room. As soon as she got into the hallway, she paused. There was a commotion so raucous she could hear it even over the music.

“I don’t care what you say, Mummy. All of these shiftless-ass adults in this house should be contributing. I am tired of doing everything around here. You let Marcus do whatever he wants and bring his lazy woman here to live with kids. She hasn’t worked in six or seven months. Then she got the nerve to say she’s a profressional hairdresser.” Sheryl stopped talking and put her hand up over her eyes. “Hairdresser? Where?” She looked around as if she were looking for something.

“She don’t bring a dime to you. The bills are piling up, the taxes on the house are not paid, and what about the crazy high light and gas? Who is supposed to do all of this? Me?” Sheryl yelled, her second-generation Jamaican accent occasionally creeping into her words.

Simmy crinkled her brow and rolled her eyes at the sound of her aunt’s loud voice. She could just picture Sheryl standing in the middle of the floor, bent slightly at the waist with her head rolling, her finger pointed and going in and out and the veins in her neck visible at the surface of her fair skin.

Sheryl was always complaining, and there always seemed to be an argument going on in the house. If it wasn’t Sheryl and Simmy’s uncle Marcus, then it was Simmy and Marcus’s kids or Marcus’s kids and Sheryl’s kids. The arguments were usually about money: the high light bills, the cable turn-off notices, or the past due water bills. Or that someone ate someone else’s food out of the refrigerator even though it was labeled DO NOT TOUCH. Or that someone wore someone else’s shoes or clothes, which Simmy remembered was the whole reason she had been drawn out of her room.

Simmy shook her head and bit down on her bottom lip as she listened. With each point Sheryl made, Simmy felt more and more like a burden. She hated living in her grandmother’s crowded house. It was times like this, listening to her aunt, that Simmy missed her parents the most.

She peeked from the corner of the kitchen door as her grandmother, Patricia, lovingly known to her children and grandchildren as Mummy Pat, sucked her teeth and continued moving her long-handled spoon in circular motions inside of the huge silver Dutch pot, mixing her curry goat gravy for the right thickness. Mummy Pat was short and wide now, but Simmy could still see some semblance of an hourglass shape, or what Jamaicans called a Coke-bottle shape, left over from Mummy Pat’s younger days.

“Oh, so you just going to act I’m not talking about the truth right now, Mummy? I am the only one in here working and bringing in money. Things falling apart around here and nobody cares. You’ve been taking a shower with no showerhead for months. Just water pouring out of the wall and that’s fine with you? And why? Because you’re waiting for me to go to Home Depot and replace it, that’s why. But, you got Marcus and Donovan coming and going like they’re Jamaican kings and bringing all their random women and kids here to eat and sleep. I can’t do this anymore, Mummy. I’m soon going to be gone from here, and the whole damn house gonna fall in around you,” Sheryl went on, getting closer to Mummy Pat’s ear.

Mummy Pat waved her hand near her ear as if she were shooing away an annoying fly buzzing around her head. But, she still didn’t say a word to Sheryl.

“Don’t act like I’m not right. Even this.” Sheryl opened her arms wide and moved them slowly over the table where Mummy Pat had at least fifteen foil pans filled with delicious West Indian dishes all sealed tight with aluminum foil covers. “It’s Labor Day weekend, and here you are spending what little money you have to buy stuff and cooking up all of this food. For what? For your hungry, no-life-having relatives to come throw their legs under the table and freeload off of you? Everybody in here is old enough to work

. You running a halfway house for no-goods and for the kids of no-goods too.” Sheryl folded her arms over her chest and pouted. “Just stupid.”

Finally, Mummy Pat slammed down the cover on her pot with a resounding clang. She rounded on her daughter, with fire flashing in her eyes.

“Let me tell you one thing here now, Sheryl,” Mummy Pat said, her thick Jamaican accent coming on strong now. She extended her metal spoon toward Sheryl for emphasis, and it moved with her words. “Don’t tell me how to run my house, hear? When you lost everyt’ing running behind a man and almost lost your mind with depression, this same house full of shiftless people was here for you. Your same brothers you complaining on went to find that man after he boxed your head and left you bruised from here to hell, and they beat his ass within an inch of life. They could’ve lost everything but, for you, they did that. You came here without a dime, and nobody said a word. Marcus was the one who would hustle up and give you a few dollars and get the kids things that they needed. Oh, yes, we banded together and put you back on your feet. Now you working for the city driving a bus and want to big up your chest? You want to be like you’re better than all of we? Nah, man, it doesn’t work that way. This is my house, and I run it the way I want. If you don’t like it, you know what to do.”

Sheryl’s head jerked like Mummy Pat’s words were an openhanded slap to her face. “Okay, so now you going to throw stuff up in my face. It’s all right, Mummy. You’re right. I know what to do.”

Simmy pressed her back against the hallway wall and closed her eyes. She let out a long breath. The constant bickering in the house did something to her mood every day. She had been reading up on depression, and she was convinced that she was depressed.

“And you.”

Simmy’s eyes popped open to find her aunt Sheryl standing in her face wearing a mean scowl.

“You can start pulling your weight around here too. Seventeen means you can work. I bet you’re still not used to living like this, Miss Princess. Your mother and father gave you everything, but where are they now? Locked up like animals. All that money and look at you now, left here for everybody else to take care of you and all your shit. You need to start contributing around here. Better use all that tits and ass you grew overnight to get a man to take care of you like your mother Carla did with my brother. She snagged Chris with her fast ass, and now he’s not around to help out his own mother, and they left you here to be a burden on top of everything else,” Sheryl whispered harshly, before pushing past Simmy and storming away.

Simmy hung her head; suddenly, she wasn’t hungry anymore. She turned on her heels and headed back to her tiny room. Sheryl had been right about one thing: her parents had given her everything when they’d had it to give.

Simmy sulked back into her room and picked up the framed picture she kept on the seat of a small, white plastic chair that doubled as her nightstand. She stared at picture and smiled. It was an oldie but goodie of her parents. Her mother was so young back then, with a fresh, innocent, dimple-cheeked smile, rocking her hair in the classic nineties high-low cut that female rappers Salt-N-Pepa had made popular, wearing two pair of gold doorknocker earrings, a neck full of rope chains, and a fly MCM navy blue and tan monogram sweat suit with a pair of brown Travel Fox boots.

Simmy’s father was eight years older than her mother and, although his facial expression in the picture was serious, the way he held her mother from behind and rested his chin on her shoulder showed that he loved her. Simmy always laughed looking at that picture of him in his tall black leather hat that sat high on his head, with his long, thick dreadlocks hiding underneath it. Simmy always thought he looked like a Dr. Seuss character in that hat. But, she loved to stare at the big gold rings her father wore on each of his fingers. One was the shape of a thick gold nugget, one was the shape of his birth country, Jamaica, and one spanned three of his fingers with the word JAH spelled out across it.

Simmy realized that, although her parents looked funny to her now, back then their outfits showed that they had money. She’d heard her family refer to them as hood rich, but she never cared about their name-calling. They’d had it all: a big house on Long Island, a different luxury car for every day of the week, and the finest clothes money could buy. Simmy was the only child, and there was nothing too expensive for her. She remembered when her father had first moved them out of their small, cramped apartment in Brooklyn.

The ride seemed so long, and Simmy asked, “Are we there yet?” about twelve times before her father finally pulled his big-body Benz up to a set of tall black wrought-iron gates with a big gold J in the center of each.

“What’s this, Daddy? Where is this?” Simmy asked, bouncing on her knees in the back seat.

“Simone. Simone, baby. You have to have patience,” her father sang, laughing at her insistence.

He pulled up to a small box and rubbed a white card against it. Simmy watched as the gates parted slowly and seemingly invited them inside. She felt like fireworks were going off inside of her and she could barely keep still. Her father drove slowly up the circular driveway and stopped the car right in front a huge set of white marble steps.

“This looks like a castle, Daddy,” Simmy gasped, craning her neck to see out of the car window.

“It’s our castle because you’re my princess. Now, c’mon, baby girl. Let’s go see,” her father said, smiling wide as he scrambled out of the car and rushed around to her side to open the door for her.

Simmy never entered or exited a car without waiting for her father to open her door. He’d told her that real men open doors for their ladies, and that had stuck with her.

When her door swung open, Simmy practically jumped out of the car. Once both of her feet were planted firmly on the ground in front of her new house, she paused with her mouth wide open and raised her head as far as it would go to look up at the house.

The gray sandstone mansion boasted eight regal white Roman columns on each side of the grand porch. The smooth, shiny white and tan speckled marble steps seemed like the stairway to heaven. Simmy was too young to even count far enough to account for all of the windows on the front of the house. In her mind, there had to be over one hundred of them. As they stood there taking it all in, Simmy’s mother walked through the huge solid cherry wood doors.

“Hey, baby girl. You like your new house?” her mother chimed, opening her arms wide.

Simmy bounded up the steps so fast the air whipped over her face and dried her lips. She jumped into her mother’s arms and squeezed her tight. “I love it, Mommy!” Simmy squealed.

“All of this for my baby,” her father said. “All of this for you, princess.”

“I miss you, Mommy and Daddy,” Simmy whispered to the picture. She pressed the glass to her lips and closed her eyes. Her shoulders slumped, and suddenly her stomach ached. Not a day went by that she didn’t think about her parents and how fast her life had changed when they’d gotten locked up. It was too much to think about, too much to relive.

She wished she could see her parents or at least be able to talk to them. Unfortunately for her, she hadn’t seen or spoken to them since they’d been arrested. She remembered asking her aunt and grandmother when her mom and dad were coming home but they refused to tell her. Instead, she was told to stay out of grown folks’ business. Now, almost four years later, she still didn’t have a clue. She had tried asking Mummy Pat again, but her grandmother was still tightlipped about it. This time around, though, Mummy Pat did explain to Simmy why she hadn’t been taken to see them since they’d been imprisoned. She admitted to Simmy that her parents made her promise to never bring her to see them. As much as it hurt them to know that they weren’t going to see their little girl for a long time, they both didn’t want her to be exposed to that environment. They wanted to keep her innocent and protected from that world.

Simmy put the picture down and grabbed her favorite book, The Color Purple, from the side of her bed. Reading was her favorite distraction from the

madness and the memories. Simmy loved to escape into books and pretend she lived in another place and time. She walked over to the long wooden platform in front of her window and sat down.

Just as she opened her book, she heard, “Simone! Simone, come down here!”

Simmy closed her eyes, clapped her book shut, and sighed at the sound of Mummy Pat calling her name like there was an emergency. Peace and quiet was surely hard to come by in that house.

“Coming, Mummy Pat,” Simmy called back. She rushed down to the kitchen.

Her grandmother greeted her with her usual warm smile. Simmy was starting to see the age show up on Mummy Pat’s face. The fine lines branching from the corners of her eyes and the deep parentheses around her mouth seemed to have appeared overnight. Mummy Pat had fair skin, hazel eyes, and sandy brown hair. Most people mistook her for Hispanic, until she opened her mouth and that thick Jamaican Patois came out.

“Simone, baby, I need some things from the store. The rice and peas needs a little zing, and I run out of coconut milk, and Scotch bonnet peppers. Please run down to the store for me, baby.”

Simmy smiled. “Okay, Mummy Pat. Anything for you.” That was true. There was nothing Simmy wouldn’t do for her grandmother. Mummy Pat was the only person in the house who didn’t make her feel like an outsider. When her parents got arrested, Mummy Pat was the one who stepped up and took guardianship of her when everyone else said no. If it hadn’t been for her grandmother, she’d have probably been in a foster home right now. Simmy was grateful for Mummy Pat, and she had the utmost respect and a great deal of love for her.

She ran back to her room, put some sneakers on, and ran out, not bothering to change or fix her hair. She figured she could shower when she got back since she was just doing a quick run to the store.

Halfway to the store, Simmy wished she had grabbed a bottle of water before heading out. It was a hot, dry summer day and the heat was blazing. She could feel the sunrays burning her caramel skin. The sun was shining so bright it was almost blinding. The more she walked, the thirstier she felt. She could feel beads of sweat forming over her upper lip. Her long, curly hair was already in a ponytail, but she could feel the hairs sticking to the back of her neck. She couldn’t wait to get back home and take a nice, cold shower to freshen up.

Girls from Da Hood 12

Girls from Da Hood 12 Girls from da Hood 14

Girls from da Hood 14 Girls From da Hood 8

Girls From da Hood 8 Obsession 3

Obsession 3 A Girl From Flint

A Girl From Flint Belle

Belle Carl Weber's Kingpins

Carl Weber's Kingpins The Finale

The Finale The Block

The Block Baltimore Chronicles

Baltimore Chronicles Working Girls

Working Girls Magic Touch

Magic Touch Around the Way Girls 11

Around the Way Girls 11 Back to the Streets

Back to the Streets Full Figured 11

Full Figured 11 Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Obsession

Obsession Girls From Da Hood 10

Girls From Da Hood 10 Back in the Hood

Back in the Hood Choosing Sides

Choosing Sides Return to Flint

Return to Flint Resurrection

Resurrection